CHILDREN OF THE JEROMINS, CHILDREN OF THE JARZĄBEKS – open play

THE CHILDREN OF JEROMINS, …..

The children of Jeromins, the children of Jarząbeks featuring the present and former inhabitants of three masurian villages;

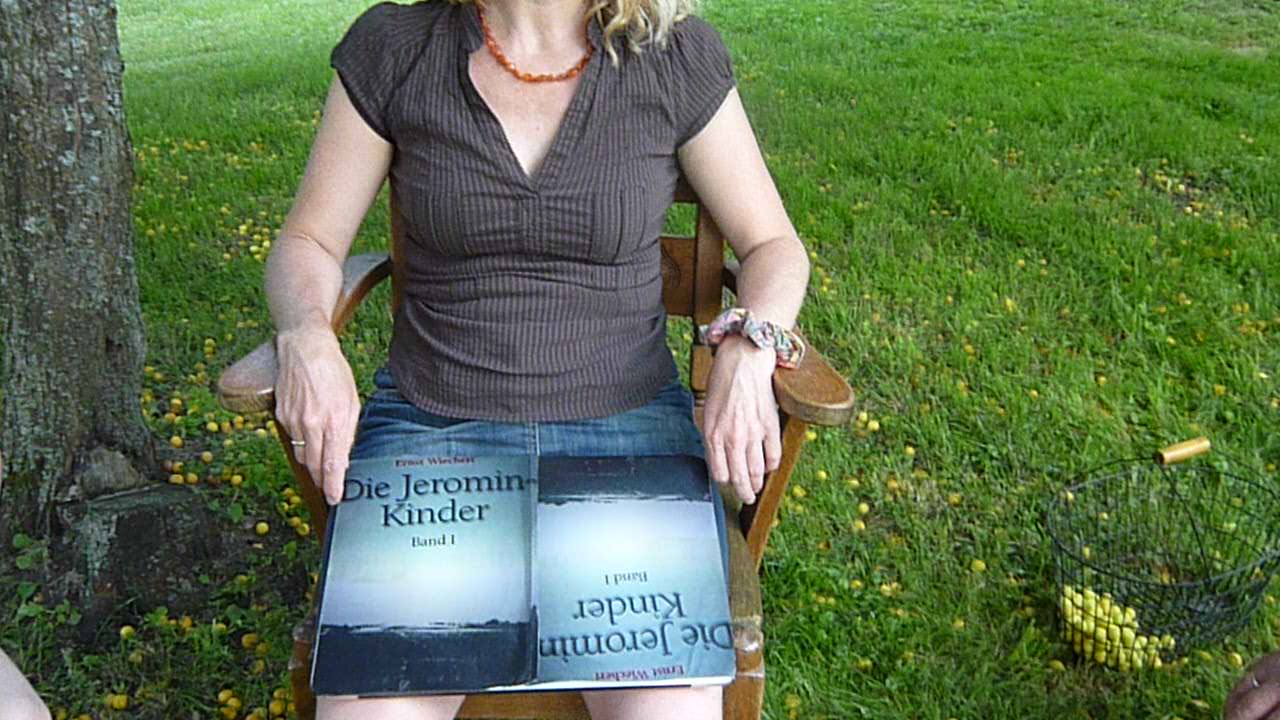

Families: the Hermans, Pietrzaks, Pilchs, Sowas, Zakrzewskis, Śliwas, Grotowskis, Zebzdas, Jeromins, Mantrybas, Berkenheides, and others. They read fragments of a novel By Ernst Wiechert: the children of Jeromins

Idea and photographs: Katarzyna Wińska

Photographs of Masuria in winter: Agata Maciak Music: Piotr Glikson

Song: Iwona Szuba, Wiktoria Pazińska

Montage: Tomek Gajewski

Production: Tomasz Wiński

The film THE CHILDREN OF JEROMINS, THE CHILDREN OF JARZĄBEKS documents rehearsals for a Bluboks Theater performance. In the summer of 2016, viewers wandered about the village of Dziubiele. They stopped in selected farmyards, whose owners and their families read fragments of a novel by Ernst Wiechert and told their own stories of settling in Masuria after the war. The protagonist’s of Wiechert’s saga are the Masurians—the residents of the village of Sowiróg, which no longer exists. This fable of a land and people from one hundred years ago, interpreted by the present inhabitants of Masuria, remains moving for the writer’s interest in every person, particularly those outside of mainstream history, who experience history in the most painful fashion. Katarzyna Wińska made and directed the film

Fragments:

[…]

She closed the door after her, then she led Jons to a small room where she slept. There was nothing there apart from an old couch with white-and-blue checked sheets, apart from a telephone, an iron stove, an old desk and a green armchair with strands of hair stuck in the upholstery of the headrests. The colorful curtains were pulled over the narrow windows, and the kitchen jug on the desk held some leafy birch branches.

Jons took a good look around, water dripping from his overcoat and onto the floor. Suddenly he backed up with a soft cry of terror. Through the half-open door leading to the shop, three impeccably beautiful pinkish faces were studying him with hollow eyes. These were wax busts with fake pearl necklaces, to match their fancy ivory-colored bras.

Jons’ companion had knelt by the stove; now she laughed softly and asked for a match. “At first I used to dream about them,” she said, “but now I’m used to them watching. We can turn them around if you like. Take off your coat, I’ll get you a cup of coffee to warm you.”

The dry kindling gave a marvellous fire, and the girl cautiously added a few lumps of coal. A glow and the first tentative warmth radiated from the small door; she knelt in front of it, stretching out her hands to feel the heat. “Isn’t it true that we don’t need much?” she softly asked.

[…]

“War, young man, is like a hailstorm. When the hail hammers the grain, the old women wail, but the wise man knows that hail has fallen ever since the days of the Prophet Isaiah. War is a craft like any other, not the cleanest one, and not particularly merry, but sometimes you have to slop the manure, haven’t you. When I see people supposedly belonging to my “kind” standing at the wailing wall, I get sick to my stomach. Our nation has a revolting tendency to spit on what has been overthrown, but others have bad tendencies as well. Only dreary people, if they haven’t been given the whip, have always been upstanding. Am I bitter? No. Just a bit tired. I’ve seen too much vermilion.

[…]

“‘New times’ are for people who write springtime articles about sighting the first cockchafer in May. But on our stage they’re always tossing manure and reaping the grain. The women and girls give birth to children, we love each other, we hate each other, we nod politely and then we murder one another. Meanwhile, there are always a few people in the gallery who dream of great justice, or of great love, just as they had two thousand years ago and just as they’ll have for the next two thousand. Hats off, Jons, to those people. They remind us that on the seventh day God erred the slightest bit, and it behooves us to fix His mistakes, at least in part.

[…]

When, after two hours, they came back to the market square, Gogun was sitting on the drawbar of the wagon like it was a narrow saddle, a whip in his right hand and a bottle in his left. “Just half an hour more, honey,” he asked. But Marta Jeromin, who looked like a nun in their midst in a black dress and white kerchief, turned away brusquely and went down the street leading past the pen in the field. There was nothing left to do but follow her, just as they always did, though they had no love for her, she was still a foreigner from the morass of Lithuania, where people’s word meant nothing and they put colored crosses in the cemeteries.

[…]

They took their kerchiefs from their heads and breathed deeply. The town was pretty, a place of sparkle and riches, marvels and promises. Soldiers marched down its cobblestoned streets, a monument with a steel eagle stood proudly and ceremoniously in the square, all the treasures of the world lay behind the glimmering panes. But their feet were unaccustomed to shoes and they hurt, the money trickled from the knot in her kerchief and the men went off getting drunk whenever they vanished from sight.

So they walked lightly on the dust of the road, which squeezed warmly between the toes, there was the good scent of young birch-tree leaves, and the beautiful and familiar cry of lapwings circling their nests. And although you never could tell what to expect at home, if a goat wouldn’t have strayed in or a pot wouldn’t have burnt, or if her husband wasn’t bringing down the roof at the inn or a little one hadn’t swallowed a button, the house would always be there, with its slanted roof and boarded windows. The lake would glisten and the pear tree would blossom on the rocky boundary line, and the cranes would clatter in the swampy meadows.

[…]